GPS

In this note we will take a look at the GPS technology, delving into the following topics:

GPS

Global Positioning System (originally NAVSTAR GPS) is a satellite-based positioning system, developed and owned by the United States government, which provides geolocation (latitude, longitude and altitude).

Architecture

The GPS system can be divided into three parts:

- Satellites: A constellation of 31 satellites that emit a constant ranging signal

- Ground stations: Ground stations that communicate with the satellites, updating its coordinates and clocks

- Receivers: Use the signals emitted by the satellites to determine their position

Earth-orbiting Satellites

The GPS system is comprised of 31 satellites in total, organized into six non-geostationary orbits, at around 26 km of altitude (12 hour period). For full GPS coverage around the world, it is only needed 24 satellites; the remainder serve as active spares, to accommodate for eventual maintenance down times of other satellites, and provide more robustness.

Ground Stations

These stations are responsible for monitoring satellites positions, and are provide two types of updates to satellites:

- Clock updates

- Satellite orbit updates

There are enough ground stations on earth so that each satellite is simultaneously monitored by two ground stations, improving location precision.

GPS Receivers

The calculation of the location is done at the receiver, using the incoming GPS signal transmitted by satellites. To calculate current location, GPS receivers need to track at least 4 satellites, but commonly track up to 12.

Algorithm

The GPS algorithm allows for receivers to estimate their position in three dimensions (latitude, longitude and altitude). This is done through estimating the positions of the satellite, and then calculating their range to the receiver, allowing therefore to know the current location.

The estimation of the satellites' position is learned using the information in the broadcasted signal; on the other hand, the distance to the satellite has to be calculated using the transit time of the signal, travelling from the satellite to the receiver.

Measuring Signal Transit Time

As we have seen, we can calculate the range from the satellite to the receiver using signal transit time. However, in order to accurately calculate this, we need the receiver's and satellite's clocks to be tightly synchronized.

The satellite's clocks, due to their usage of atomic clocks and constant synchronization with ground stations, are very accurate and less of a problem; however, GPS receivers use low-cost crystal oscillators, that will introduce a bias to the signal transit time, making it look shorter or longer. The solution to this relies on the fact that this bias is the same for all satellites, and as such we can treat the bias as a extra unknown in the location calculation.

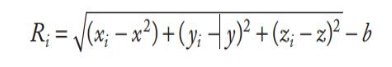

Fig.1: GPS receiver's location equation ( is the bias introduced by the inaccurate GPS clock)

Fig.1: GPS receiver's location equation ( is the bias introduced by the inaccurate GPS clock)

If we had perfect clocks, the variable would not exist, and we could in fact calculate the correct location using only 3 satellites; however, it is not possible to have perfect clock synchrony, and therefore 4 satellites need to be used.

In case more than 4 satellites are available, the information provided by the additional satellites is used to eliminate error in the location estimate.

Using this basic algorithm, commercial GPS units can estimate location with a media accuracy of 10 meters.

Satellite Range Estimation

To calculate the range between satellite and receiver, satellites transmit GPS signals modulated by a specific PRN code. PRN stands for Pseudo Random Number, and it corresponds to a sequence of seemingly random bits, but that are specific to each satellite, and are known to the receiver.

To calculate the range, GPS receivers will first identify the satellite transmitting a certain GPS signal, and then calculate their PRN code; the time delta between the received code and the locally calculated code corresponds to the signal transit time. Finally, to calculate the range, simply multiply the transit time by the speed of light.

The theoretical accuracy of the range estimation is:

- 3 meters for civilian GPS

- 0.3 meters for military GPS

Satellite Coordinate Estimation

GPS receivers obtain satellite's position information from the transmitted GPS signal; encoded into the PRN code a navigation message. The navigation message contains the following parameters:

- Coordinates of the satellite, according to a function of time

- Satellite clock correction parameters

- Satellite directory

- Constellation health status, and

- Parameters for ionospheric error correction

To speed location calculation at the GPS receiver:

- Satellite coordinates and clock offset are repeated in the navigation message every 30s

Errors and Biases

Ranging errors

There are three potential sources of errors for range calculation:

Satellite's Clocks

The satellite's use very precise atomic clocks. However, these can still accumulate an error of up to 17 ns every day. Due to this, ground stations communicate with the satellites, to keep the clocks synchronized.

Satellite Coordinate Errors

These occur due to the fact that satellite position models fail to account for all the forces acting on a satellite; this can originate an error of up to 2 meters.

This is countered by using precise orbit data, available on the internet.

Ionospheric Delay

==Ionospheric delay is the dominant source of GPS ranging errors.== This happens due to the interaction of ionized gases with GPS signals, and will vary according to time of year, region of the atmosphere, etc...

To counter this, ionospheric delay models were developed, allowing to reduce ionospheric range error to 4 meters.

Location errors

The quality of the GPS location estimation depends on:

- How well the tracked satellites are spread across the sky

- In general, satellite geometry improves as the distance between satellites increases

Real-Time Differential GPS

While the previous GPS mechanism that we saw (basic GPS) allowed for 10 meter accuracy, certain use cases might require greater accuracy. To achieve this, extensions to the GPS system were created, in order to provide additional accuracy to the system. One of this extensions is Real-Time Differential GPS.

Real-Time Differential GPS (DGPS) relies on the fact that satellite clock and position errors, as well as ionospheric delay are the basically the same, independently of the current location or time (high spatial and temporal correlation). For example, the error in a given satellite's clock will be the same, whether we are trying to measure current location in Lisbon or in Porto; likewise, ionospheric interference will be similar, in a given interval of time (today and tomorrow, for example).

Due to this, we can have additional reference stations, and inside have GPS receivers at known locations (i.e., we know the exact latitude and longitude of where these GPS receivers are located). These GPS receivers will then compare their calculated location using GPS signal with their known location, and infer the errors that exists in the emitted signal (these errors are relative to satellite clock and positions, and ionospheric delay).

The corrections that are made are then transmitted, over wireless signal, to nearby GPS roving units (for example, GPS in a car), so that they can more accurately calculate their ranging measurements.

Examples

Maritime DGPS

It consists of a network of stations, installed at lighthouses across the world, providing DGPS corrections via wireless signal (285 - 325 KHz signal). These transmissions are available at no cost, but require an augmented GPS receiver in order to be used.

Wide Area Augmentation Systems (WAAS)

This system comprises 25 ground stations, performing DGPS calculations. The corrections are then transmitted to 4 geostationary satellites, that are then responsible for re-transmitting the corrections worldwide.

Real-Time Kinematic GPS

Real-Time Kinematic GPS relies on the GPS signal's cycles to calculate the distance between a satellite and a GPS receiver.

For example, between a satellite and a receiver, there is a certain number of full signal cycles plus a fractional cycle. While the fractional cycle can be easy to calculate, the number of full cycles is ambiguous. In order to correctly calculate the number of full cycles that happened in a transmission, simultaneous measurements are taken at two separate receivers (there are multiple techniques).

After receiving the base's measurements and resolving the ambiguity, roving RTK receivers obtain centimeter-level precision.

RTK systems are very expensive, and require line of sight between the coordinating GPS receivers.

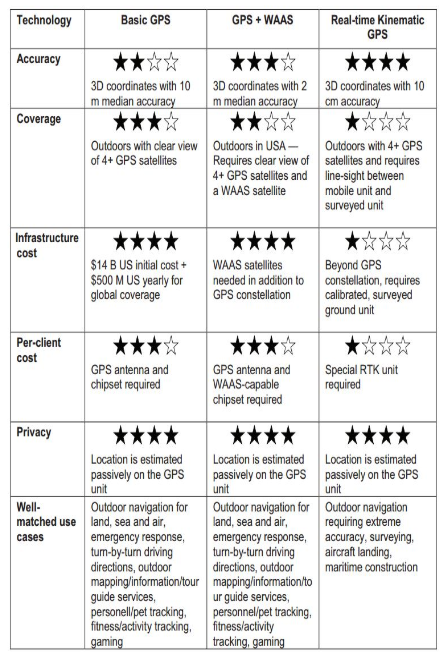

Comparison

Fig.2: Comparison between GPS techniques

Fig.2: Comparison between GPS techniques